Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

A Forceful History of Black Resistance

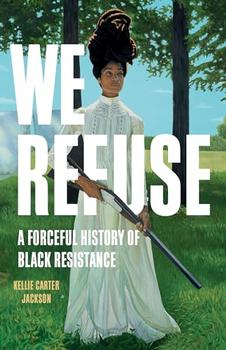

by Kellie Carter JacksonThe cover image of Kellie Carter Jackson's We Refuse: A Forceful History of Black Resistance is designed to provoke a response. A Black woman in an ankle-length white ruffly dress with dreadlocks piled atop her head holds a long shotgun pointed to the ground, her expression a steely gaze. The hyper-realist painting, by artist Taha Clayton, depicts a Black person preparing to use force, if necessary, to stand her ground.

The feeling the image might produce in some viewers, Jackson's exceptional work of historical exploration suggests, is one of fear or revulsion, as it is in defiance of the expectations and preferences of a white supremacist culture. A white supremacist society encourages people of color to limit their protest methods to those of nonviolence because this is what is required to maintain that supremacy. These methods can be incredibly slow to generate results, or even completely ineffectual.

The association many have for the violence/nonviolence dichotomy is the disparate philosophies of civil rights activists Martin Luther King, Jr. and Malcolm X. Jackson goes far beyond this simplistic model to demonstrate that questions of political violence have echoed throughout centuries of world history, and that some manifestation of force is often the only effective means of changing a system rotten to the core with racist oppression. Nonviolent protest depends on sympathy and receptivity from the system and its upholders. Jackson quotes Black Panther Party member George Jackson: "It presupposes the existence of compassion and a sense of justice on the part of one's adversary."

The chapters in We Refuse focus on five distinct (though often enmeshed) forms of Black resistance to white supremacist oppression: revolution, protection, force, flight, and joy. In the opening chapter, Jackson focuses on the Haitian Revolution in particular as an example of a radical and systemic transformation of a society through the use of violence, detailing the overthrow of the French colonizers by an armed, organized, and motivated populace (and led by the indefatigable Toussaint Louverture). She contrasts this event with the American Revolution, which she declares a misnomer given that its instigators and soldiers fought for the freedom of only a segment of society: "Washington was not fighting for revolution; he was fighting for independence from Britain."

The anecdotes throughout the book focused on individual courage are often the most dynamic. The chapter on force narrates the stories of Carrie Johnson, a teenage girl who defended her home with a gun from a white mob during a riot in Washington, D.C.; and Daisy Bates, who established her house as an armed and fortified compound to protect the first students integrating Little Rock, Arkansas's Central High School (see Beyond the Book). But Jackson skillfully shows that resistance must be a group endeavor to succeed. In the chapter on protection, we meet members of the Lancaster Black Self-Protection Society, which hid and assisted people fleeing enslavement in Christiana, Pennsylvania. While member Eliza Parker is singled out for her bravery in a gun fight with a deputy marshal and an enslaver, it was the effort of the group, including white Quaker allies who arrived after a call for backup, that ensured escape was possible. And force, Jackson explains, is not always violent: "Force can be a strike. Force can be a boycott. Force can be a vote. Force can be armed self-defense."

Jackson ends the book on the subject of joy, explaining how it is perhaps the most revolutionary means of preserving Black life, and a force in itself that detonates the tenets of white supremacy:

"The joy of laughter, food, dance, dress and adornment, rhetoric, play, and art can be employed to dispel and destroy whiteness as supreme … Anti-Blackness...perpetuates beliefs that Black people are subhuman and deficient. Black joy produces the antidote to the degeneration and erosion of Black life … Roller skating, fishing, singing, teasing, sharing, resting, vacationing, getting dressed up, shopping, bathing, working, or quitting—if it compels joy, then it refutes the idea that Black people are subhuman."

The remarkable historical events and anecdotes conveyed support Jackson's claim that resistance must be multifaceted and include an arsenal of forceful tactics. They offer inspiration and practical tips for resistance to oppression that is ongoing (e.g., filming police encounters with Black people as a bystander). We Refuse is an academic work that engages critically and energetically with historical scholarship, but it does more than just create an informed and interesting argument. It establishes what we must do, singularly and collectively, to dismantle systemic racism and ensure that the burgeoning of Black life and Black joy need not be an act of protest against the norm — not an aberration but an expectation.

![]() This review

first ran in the June 19, 2024

issue of BookBrowse Recommends.

This review

first ran in the June 19, 2024

issue of BookBrowse Recommends.

If you liked We Refuse, try these:

by Ashley Hope Pérez

Published 2025

A dazzling YA anthology that spotlights the transformative power of books while equipping teens to fight for the freedom to read, featuring the voices of 15 diverse, award-winning authors and illustrators.

by Ta-Nehisi Coates

Published 2024

The #1 New York Times bestselling author of Between the World and Me journeys to three resonant sites of conflict to explore how the stories we tell—and the ones we don't—shape our realities.

Finishing second in the Olympics gets you silver. Finishing second in politics gets you oblivion.

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.