Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

A Novel

by Dinaw MengestuWhile suicide is the seminal event in the novel Someone Like Us, its characters anchor the story, shedding light on male anxiety and fragility. Ethiopian American writer Dinaw Mengestu portrays a relationship between two men as loyal, complicated, and gentle. While Samuel struggles to stay afloat as a cab driver in Virginia, his son Mamush is drowning in his marriage in France. The connection the men have with one another as they experience dissatisfaction is the putty that holds the story together.

The novel begins with Mamush arriving at his mother's house two days before Christmas. His mother announces with sadness that Samuel has died in his garage. Mamush is stunned into silence and grief while his mother clings to a familiar Ethiopian sermon, the idea that the death can be explained by a government conspiracy.

From there Mengestu untangles the past experiences of both men, and how things fell apart. The chapters alternate between Virginia and Chicago, places where the characters live parallel yet dissimilar lives as first and second generation immigrants. While a specific timeline isn't attached to the chapters, Mengestu shows the story through the perspective of Mamush, who is introduced to Samuel at the age of six without knowing the stranger is his father: "When my mother opened the door and found him on the other side, she seemed more resigned than alarmed to find him there…She never shared how and why she and Samuel had left Ethiopia, nor did she ever say why, years later, he followed her to Chicago, and then to the suburbs of Washington, DC." The message that Samuel is acceptable but only in slender doses, like a rich caramel syrup, is received. That he can't be trusted to impart wisdom only makes Mamush more attracted to him.

This is a story about adaptation as much as it is about assimilation. Mamush's mother owns a house she can't afford and this links her to her adopted country with its millions of debt-happy citizens. Samuel's failed cab business dreams cost him in far worse ways. He rarely sleeps. He self-medicates with an array of substances and is often enraged and paranoid. It is left to his wife, Elsa, to rationalize his terrible wrongs. "You understand," Elsa tells Mamush, "he isn't himself these days. He's sick. He's in pain all the time." The emotional cost of leaving his country is a continual piercing, like tiny holes through the skin, until the scabbing is too much to bear.

The risk in this kind of story, dark even with its lyrical passages, is that the reader will fit the suicide arc into a generic template of unhappiness, a one-size-fits-all characterization, and not recognize it as a silent hazard of immigration. Immigrants may hold on to their secrets because they have to pretend their decision was worth it. Mengestu has an authentic connection to this material, being Ethiopian American himself, and is skilled at writing male anxiety, so readers might wonder why he abandons us to figure out for ourselves what's wrong with Samuel based on the clues he provides. But maybe it is not we as readers who are abandoned but the immigrant characters who are forced into isolation.

Mumash, for instance, lives in France with his wife Hannah, a photographer. One day Hannah discovers Mumash's drug paraphernalia and challenges him to get his life together. But helpless men can be their own worst enemies and the women who love them dismissive of dark secrets. Here's what I think Mengenstu wants us to know about second generation immigrants: They are enslaved in a different way than their fathers but the end result is the same. Their search for belonging comes up short.

American-born Mamush wants the kind of acceptance that's often missing if you're non-white. In college, he creates the pseudonym Christopher T. Williams, which he uses as a personality he can climb into and out of when it suits him, a capitalistic costume, someone who can fall from grace. The ability to fall would indicate a starting point denied Mamush and most of those from immigrant families. While wanting—lusting after—the exterior veneer of ordinary American, he is less faithful to his ancestry, including the Amharic language, which he doesn't speak. Samuel uses this as an opportunity to other him, to remind him he is a betrayer of his family. This is ironic, because Samuel, who can speak Amharic fluently, wants the same kind of acceptance as Mamush but lacks the American-born capitalist insight to make the necessary compromises.

And so, what we are left with as we take in these characters and their complications is the truth of men like them. The necessary fluency to complete their dreams depends on the skill of making themselves visible and then remaking themselves all over again, and in a country that believes you are what you earn, this still might not be enough. Samuel and Mamush, a generation apart, are the same sort of man: lonely, nihilistic, and perceived as replaceable, a combination that can and often does lend itself to a quiet kind of tragedy that goes unnoticed. That's a part of nativism that is baked into us: Ignore the invisible. The Nigerian writer Wole Soyinka wrote poems on toilet paper in prison. That's the experience of Mamush and Samuel in America. Culturally isolated and yet trying to express their art.

Someone Like Us is a story that ultimately lives beneath the skin of its characters, a jigsaw puzzle with a missing piece. The air we breathe is the air that makes others cough. Mengestu's novel is an examination of an absurd contradiction. Often, loving a country isn't reciprocated by the country loving you back. Choices, then, remain bleak. The wound grows, without interruption.

![]() This review

first ran in the July 31, 2024

issue of BookBrowse Recommends.

This review

first ran in the July 31, 2024

issue of BookBrowse Recommends.

If you liked Someone Like Us, try these:

by Maame Blue

Published 2024

An internationally award-winning writer makes her triumphant American debut in this emotionally powerful story—a potent blend of Queenie and The Vanishing Half—about a woman's journey to uncover a foundational family secret from the childhood she does not remember.

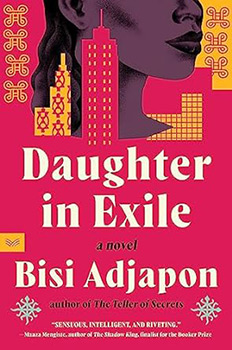

by Bisi Adjapon

Published 2024

The acclaimed author of The Teller of Secrets returns with a gut-wrenching, yet heartwarming, story about a young Ghanaian woman's struggle to make a life in the US, and the challenges she must overcome.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.