Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

Fiction

by Tony TulathimutteA young man identifying as a feminist tumbles down the incel rabbit hole after a lifetime of sexual and romantic rejection. A woman alienates friends and potential future partners after a one-night stand fails to result in a long-term relationship. A gay man is unable to explain his sado-masochistic sexual proclivities to his boyfriend. Tony Tulathimutte's short story collection Rejection explores these and other situations to hilarious effect.

"Ahegao, or The Ballad of Sexual Repression," the story of the gay sadist, and another story, "Main Character," are connected because their protagonists are siblings, and also because they both concern characters who attempt to ward off rejection by rejecting the world they believe would shun them. In the former, the protagonist Kant takes a passive approach to dating and relationships that ensures he will never find what he needs because his insecurities about his racialized identity have created a psychosexual vacuum that he prefers to feed with pornography rather than examine and potentially heal from. His sibling Bee in "Main Character" refuses to identify at all, as anything, ever, likely in part as a response to having witnessed the bullying Kant endured in childhood. Instead, Bee slips into the anonymity afforded by the internet and duplicates and proliferates a series of manufactured identities in the form of bots and troll accounts existing purely to stir up fake controversy. While it's easy to sympathize with Bee's desire to eschew categories of gender and racial identity, this character's account of social media fabrication becomes grating and tedious, like listening to an acquaintance describe a meandering dream.

While some stories are more dynamic and some characters more compelling than others, the collection is uniformly hilarious and Tulathimutte exhibits exceptional powers of description. The male feminist discovers an online community with whom he identifies — those "willing to declare unapologetically that narrow-shouldered feminist men are the most oppressed subaltern group." Alison of the one-night stand adopts a raven, which "turns out to be a flesh-ripping fiend with a knife for a face" that "smells like soiled hospital clothes" and survives on a diet of "wet microwaved rats."

The author cleverly ends the collection with a story called "Rejection," which feigns to be a letter from a publisher rejecting the manuscript that has become the very book the reader holds in their hands. It is a winding exercise in self-referential and self-deprecating humor but it also astutely explores the discomfort surrounding author intention that readers might feel after engaging with these stories. To what degree are we supposed to feel empathy toward these characters? To what degree are we meant to simply laugh at their failures and fates? It's easy to condemn, for instance, the man in "Our Dope Future" who essentially holds his girlfriend hostage while attempting to live out a white supremacist fantasy. But what about Kant and the male feminist and Alison?

The reader might feel comfortable laughing at them because Tulathimutte is skewering a particular kind of person — one who is thin-skinned in the face of rejection and capable of burning their life to the ground in response. "Let it go!" we want to shout at them as they alienate everyone around them and withdraw into the self-imposed exile of, for instance, incel forum posting or exotic bird ownership. The less overtly repugnant characters seem to be comical cautionary tales about what can happen to a person who refuses to process and move on from rejection. The male feminist feels entitled to attention from women because he is a self-professed ally but fails to engage in genuine self-reflection about why no woman wants to date him. Alison slides into casual racism and mild stalking when the man she is interested in does not reciprocate her feelings. But what of Kant? Is sexual repression a quality on par with racism and misogyny?

Tulathimutte invites us to ask ourselves why we might sympathize with the plight of a certain type of rejected person and not another, and at what point that sympathy might dry out. There is a sheen of uneasiness over these proceedings for any reader who engages on more than a superficial level. Superficially, the collection is very, very funny and cleverly constructed, and those uninterested in engaging in self-reflection will still reap plenty of rewards (as in life, perhaps more than the doggedly introspective).

![]() This review

first ran in the September 18, 2024

issue of BookBrowse Recommends.

This review

first ran in the September 18, 2024

issue of BookBrowse Recommends.

If you liked Rejection, try these:

by Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky

Published 2024

A young, lonely man strolls the streets of St. Petersburg contemplating his solitude when he happens upon a young woman in tears.

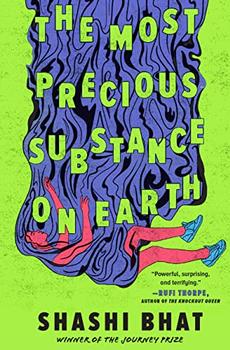

The Most Precious Substance on Earth

by Shashi Bhat

Published 2023

Journey Prize winner Shashi Bhat's sharp, darkly comic, and poignant story about a high school student's traumatic experience and how it irrevocably alters her life, for fans of 13 Ways of Looking at a Fat Girl, Girlhood, and Pen15.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.