Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

The Secret History of a Murder in Mississippi

by Wright ThompsonThe barn doesn't reek of catastrophe at first glance. It is on the southwest quarter of Section 2, Township 22 North, Range 4 West, surrounded by cypresses, sequoias, and the bayou. The barn looks like every other barn in Sunflower County, Mississippi with weathered boards and a dull patina. When Jeff Andrews purchased it, he was unaware of its menacing and symbolic past, as the place where fourteen-year-old Emmett Till was tortured, beaten, brutalized, and lynched.

The barn's very presence reopens a tattered wound that Wright Thompson thinks of as a blessing and a curse. Thompson is mostly known for his long-form articles for ESPN.com, where he is a senior writer. He has penned a masterful work in The Barn: The Secret History of a Murder in Mississippi, examining the death of a child while also questioning Mississippi culture and the history of the land where the murder took place, which is his home state. Thompson eloquently finds a middle ground to tell the story of Emmett Till and the story of Mississippi — a balancing act to be sure, mapping both gods and monsters.

For those who don't remember or have never heard, Chicago-born Emmett Till was visiting his great uncle Moses Wright in Money, Mississippi. Wright, the son of slaves, had once owned land until the cotton market crashed, which forced him into the oppressive contractual agreement of sharecropping. Had that not happened, he would have probably fled Mississippi too. But he was stuck and, in the summer of 1955, his great nephew Emmett came to visit and meet his southern relatives.

Emmett loved rural life. Milk coming out of a cow. Uncle Moses eating brains and eggs for breakfast, and on a good day, Moses making his own sausages and hanging them in the smokehouse. Mississippi was a simple place for a well-loved Chicago kid unaware of the code of conduct he was supposed to follow. Or, how white women, with the stories they told their fathers, brothers, and husbands, could sign a death certificate for an innocent black boy.

What you think happened to Emmett Till depends on who or what you believe. The white men who were acquitted of his murder (though they later confessed to the crime). Or the copious facts like those Wright Thompson has uncovered in his research. There's a third option as well. Common sense. A black boy leaves Chicago healthy and comes back in a coffin, and comes back at all only because the governor of Illinois demands the sheriff turn over the body. Mamie Till refused to close her son's casket and encouraged photojournalists to snap his picture and publish it in newspapers all over the world to show what racial violence looked like on a teenager whose bloodied, battered, and puffed-out face categorized a generation of dead and beaten innocents. "Let the world see," she demanded.

The question Wright Thompson had to wrestle with before beginning to write about the barn where Till was tortured was simple: Why write a book about the Till murder seventy-plus years after the fact? What do we need to know about the story that we don't already know? Till was kidnapped at two in the morning, held hostage, tortured, lynched by Roy Bryant and J.W. Milam, then dumped into the Tallahatchie. Emmett Till is dead. His mother Mamie is dead. His killers got off scot-free. Carolyn Bryant recanted her lie about Till whistling and making sexual advances toward her at Bryant's Grocery and Meat Market. (Bryant never suffered any consequences for her fabrication.) She is dead too. So, what's the point?

Thompson believes details matter. "The tragedy of humankind isn't that sometimes a few depraved individuals do what the rest of us could never do. It's that the rest of us hide those hateful things from view, never learning the lesson that hate grows stronger and more resistant when it's pushed underground."

And yet, even with that intention, it's not the story of Emmett Till itself that shapes The Barn into its greatness. Thompson offers a cogent argument that the culture of Mississippi murdered Till just as much as the cohort of men in the barn. He presents as evidence grains of racism like soil in which hate is an organic fertilizer. It reveals itself first in the mud and then in the root, and then grows the tree and bends the leaves and permeates the air and water and men swallow it.

We learn that black residents have renamed the Tallahatchie River the Singing River because the lynched were also the drowned. Their souls sing about their pain. The land that the barn is on is land the government evicted black people from in order to give it to white men like Jeff Andrews' grandfather to even out the economic plight of the Great Depression.

This, too. In 1871, sixty members of an insurgency led by Nathan Bedford Forrest, former Confederate general and first Grand Wizard of the KKK, invaded the home of black political leader Jack Dupree in Monroe County, Mississippi. They dragged him out the front door, stripped his clothes off and knifed him. They slit his throat, then cut out his heart and intestines before throwing his corpse in the creek. Then they beat local independent farmers who were renting land and working it. The goal was to force blacks to become sharecroppers. When Vicksburg voters elected a black sheriff in 1874, white mobs killed fifty black citizens. When they were found guilty, a judge reversed the indictments. The worst part was how the Supreme Court was complicit, agreeing with the judge and normalizing Klan violence as self-defense.

"The story of Till's death is the story of the rise and rot of a tribe of people of which I am one," Thompson writes, and this feels melancholic juxtaposed against the racial violence romanticized in Mississippi. There are a lot of tragic stories he tells but one stuck with me. A beating of a black man in a store, his skull exposed, and all the white men laughing.

What does this have to do with the barn? Everything. It's the celebratory subtraction of human beings. During his research for the book, Thompson met with Jeff Andrews, a dentist, to get a glimpse of the barn, and Andrews was thrust into the role of tour guide. "That's right there where he was hung at," Andrews informed him as they looked up at a corroded beam. Andrews is patient with members of the Till family, who every now and then want to visit the barn as a requiem to their fallen relative, but he isn't quite sure why it really matters. He's the fourth owner of the barn since the Milam family; he doesn't cosign the past as being prologue. For that reason he is part of the audience Thompson is appealing to, The Barn a reminder of the history he owns.

Thompson exposes blatant lies that land quietly. Emmett Till did not die in Money, Mississippi. He was executed in a barn in Drew, in Sunflower County. The men on trial for his murder weren't rogue racists acting on impulse. It was a coordinated and planned attack with powerful men behind the scenes who made sure their names were kept out of the news. The gun hasn't been melted down and isn't in a museum but in a safety deposit box.

The Barn is a breathtaking book and story and history. Its brilliance is its light. Its brilliance is its darkness. The historic recurrence of anti-black violence is the broad stroke Thompson paints so elegantly, which is the irony. His gentle prose allows us to grasp what happened that horrible day in August. The barn where Till died, in Thompson's words, is like a vessel. One that restores truth back to the earth.

Thompson's insights and quasi-shame of being a child of the Delta build a story that is wholly unforgettable, but then, what creeps upon you as you absorb one page after the next, and exhale and swallow, and read another passage, and notice the lack of mercy, is that this is all true.

This really happened.

![]() This review

first ran in the October 16, 2024

issue of BookBrowse Recommends.

This review

first ran in the October 16, 2024

issue of BookBrowse Recommends.

If you liked The Barn, try these:

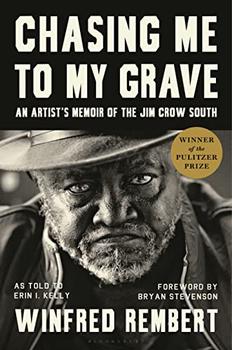

by Winfred Rembert

Published 2023

Winfred Rembert grew up in a family of Georgia field laborers and joined the Civil Rights Movement as a teenager. He was arrested after fleeing a demonstration, survived a near-lynching at the hands of law enforcement, and spent seven years on chain gangs.

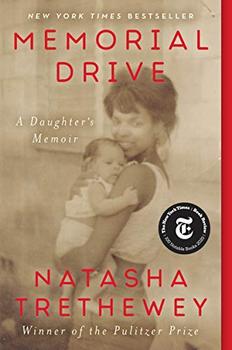

by Natasha Trethewey

Published 2021

A chillingly personal and exquisitely wrought memoir of a daughter reckoning with the brutal murder of her mother at the hands of her former stepfather, and the moving, intimate story of a poet coming into her own in the wake of a tragedy.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.