Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

A Novel

by Ali SmithA four-time finalist for the Man Booker Prize, Smith is perhaps best known for her seasonal quartet, a series of novels, each named for a season of the year, produced as a sort of experiment in writing on and about "the surface of now," as she has described it. Written and published on a radically accelerated schedule, each novel responds almost in real time to the crises of the day, from Brexit and the refugee crisis to Covid and climate change.

Gliff, Smith's thirteenth novel, is also a commentary on our contemporary political landscape, but it takes place in the future, describing a brutal surveillance state that is a chillingly plausible extrapolation from our current reality—an increasingly hostile world of growing intolerance and authoritarianism, social divisions and inequalities, data tracking and algorithmic control. If the novels of the seasonal quartet show us the "surface of now," Gliff shows what's just beyond—where we're headed and what's around the bend. Needless to say, it's not a place we want to go.

Set in the near future in an unspecified location that reads as Britain but could be a stand-in for anywhere in the Western world, Gliff tells the story of two siblings, the evocatively named Briar and Rose, who are forced to fend for themselves when their mother is called away to tend to a family emergency. At first, the details of their situation are sketchy, but the vibes are distinctly dystopian. As the novel opens, the children have gone to meet their mother outside the luxury hotel where she has begun working to cover for her ill sister. She signals uneasily with her eyes, puts her fingers to her lips to silence an inopportune comment. Surveillance cameras and microphones are everywhere.

Things take a menacing turn when the children return home with Leif, their mother's boyfriend, and find a bright red circle painted around their house (see Beyond the Book). It's the unmistakable sign that they have been marked as "unverifiables," an underclass of citizens who have been designated as undesirable and cast to the margins of society. When another painted red circle appears around their campervan and Leif disappears, Briar and Rose are forced to go into hiding on their own to avoid the customary fate of unverifiables—getting rounded up by the state machinery, sent to a reeducation center, and deployed to a brutal work camp.

In the totalitarian system in which Briar and Rose live, the grounds for being declared unverifiable are myriad, including ethnicity, religion, disability, or any other trait deemed objectionable or inconvenient. Most, we learn, have been unverified for transgressions of speech or thought—for example, "saying out loud that a war was a war when it wasn't permitted to call it a war," "writing online that the killing of many people by another people was a genocide," or "defaming the oil conglomerates by saying they were directly responsible for climate catastrophe."

Smith never explicitly says why Briar and Rose have been unverified, but readers are left to surmise that it has something to do with their idealistic mother's status as a whistleblower who exposed the toxic truth about the products of a powerful weedkiller company—or perhaps her general refusal to conform to social expectations. In this tech-mediated society, adults walk around with their eyes glued to their devices, and children no longer go to school. Instead, they wear "educators" on their wrists—special smart watches that also double as personal spying devices. The children's independent-minded mother, however, remains stubbornly old-school, refusing to get a smartphone and teaching her children to value obsolete things like books. "Our mother thought smartphones were liabilities," Briar says, "a device that means you see everything through it."

Narrated by Briar, a precocious teen who is the older of the two siblings, Gliff weaves in recollections from the past to fill in these details from the children's backstory. There are also repeated time jumps to a period five years in the future, when the siblings have been separated. Briar has recently been released from a reeducation center. Rose's fate and location are unknown. Having managed, against all odds, to become reverified, Briar now works as a supervisor in a sweatshop-style factory, enforcing the system's draconian rules against the unverifiables who toil there—until a chance encounter with a character from the past unleashes a flood of suppressed memories and provokes a daring act of resistance.

An ominous vision of a dystopian future of techno-totalitarianism, Gliff is a cautionary tale all too relevant for our current day—a time when surveillance technology is increasingly prevalent, algorithms control the information we see through our social media feeds, a handful of tech oligarchs have growing political sway, and democratic institutions are in decline worldwide.

The book deals with dark topics—oppression, inequality, prejudice—but it is also about individual resilience, human connection, and meaning. Those are heavy themes, but Smith writes with a light touch, lacing the narration with playful cultural references, humor, puns, double meanings, and whimsical flourishes. Indeed, elements of the book read like a fairy tale or fable. Navigating through a landscape of perils on their own, the two siblings evoke Hansel and Gretel—except that, instead of a wicked witch, they encounter a fairy godmother in the figure of Oona, a spunky, kindly old woman who resists the state's surveillance apparatus.

Gliff's title refers to the name Rose gives to a horse she befriends—an animal described in almost mythical terms, adding to the fable-like feel of the book. Later, stumbling across a dictionary in an old abandoned school library, Briar discovers that "gliff" is in fact a real word, a Scottish term with a long slew of meanings that take up a page and a half. One of the definitions, Briar is thrilled to learn, is "a substitute word for any word."

"You've actually called him something unpindownable," Briar reports excitedly to Rose. "You've given him a name that can stand in for, or represent, any other word, any word that exists. Or ever existed. Or will. Because of what you called him, he can be everything and anything." For Briar, this makes the horse a symbol of boundless possibility—and, in the end, an object lesson in meaning-making.

Like the algorithms and data that dictate what people are allowed to be and do in the repressive system depicted in the book, the definitions we attach to things are an attempt to pin them down, restrict what they can mean. Yet the horse remains untethered to human definitions, able to escape any meaning we impose on him. This is not only because of the name Rose gave him, something that effectively can mean everything and anything and so, in some sense, nothing. ("It's like you've both named him and let him be completely meaning-free!") More fundamentally, Briar comes to realize, it's because the horse doesn't need any name in the first place. What humans name him or indeed whether we name him at all has no bearing on the horse's reality—just as the horse's world is no less real because the horse himself has no words with which to describe it.

Fans of speculative fiction who like meticulous worldbuilding may find the future society described in Gliff to be underspecified—impressionistically rendered rather than fully articulated. The book also leaves some key plot elements unresolved, including what happens in the intervening years before the five-year jump to the future. No doubt many of these details will be spelled out in a companion novel Smith plans to release later in 2025 (reflecting her characteristic love of word play, the book is to be called Glyph). Other gaps in the narration are perhaps deliberate. After all, as Briar's ruminations suggest, one message of the book is that there is a kind of freedom in ambiguity, in what's left unsaid, in the undefined spaces that leave room for new meanings to open up.

Like all tyrannical regimes, the surveillance state in Gliff seeks the ultimate power to control the currency of meaning, to define who people are and what counts as reality, and to erase any space for individual meaning-making. To Rose, with the innocent ingenuity of a child, the solution is simple: "Bri, who is really good with machines and tech, is going to invent a technology that eats all the data that exists about people online so people can be free of being made to be what data says they are."

![]() This review

first ran in the February 12, 2025

issue of BookBrowse Recommends.

This review

first ran in the February 12, 2025

issue of BookBrowse Recommends.

If you liked Gliff, try these:

by Laila Lalami

Published 2025

READ WITH JENNA BOOK CLUB PICK AS FEATURED ON TODAY ● From Laila Lalami—the Pulitzer Prize and National Book Award finalist and a "maestra of literary fiction" (NPR)—comes a riveting and utterly original novel about one woman's fight for freedom, set in a near future where even dreams are under surveillance.

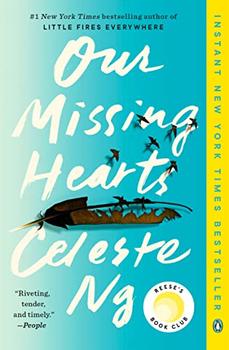

by Celeste Ng

Published 2023

From the #1 bestselling author of Little Fires Everywhere, comes one of the most highly anticipated books of the year – the inspiring new novel about a mother's unbreakable love in a world consumed by fear.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.