Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

A Novel

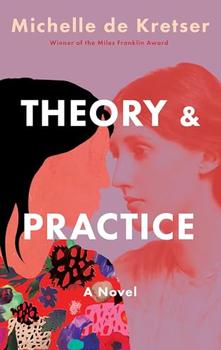

by Michelle de KretserIn Michelle de Kretser's novel Theory & Practice, the first-person narrator undertakes graduate studies in Melbourne in 1986, when academia is steeped in French poststructuralist theory — referred to through most of the book simply as "Theory." She explains how literary critics applying Theory refer to themselves as "torturers," poking and prodding at a text to discover the hidden meaning behind it: "When it was revealed and the text was in pieces, the critic had won." The narrator, a critic herself, is writing her thesis on the construction of gender in Virginia Woolf's work, a concentration she struggles with after discovering a racist description of E. W. Perera, a Ceylonese barrister active in the Sri Lankan independence movement, in the author's diary. A Sri Lankan immigrant to Australia familiar with Perera's legacy, the narrator sets about reconciling her admiration for Woolf with the writer's racism through her own interpretation of the novel The Years (see Beyond the Book).

Shortly after arriving in Melbourne, the narrator becomes involved with Kit, a man who claims to be in a "deconstructed relationship" with his girlfriend Olivia. Unsure of whether or not Olivia knows she is seeing Kit, the narrator experiences their affair as an uncertain and morally gray conundrum, not unlike her now-twisted relationship with Woolf. Although preoccupied with deciphering Kit's feelings for her and the meaning behind them, she is even more preoccupied with Olivia, whom she eventually begins stalking.

Intersecting with this thread and that of the narrator's studies are anecdotes involving the narrator's friends, along with consistently hilarious messages from her mother in Sydney: "I missed hearing your voice on Sunday but I understand that you had to unplug the phone to study undisturbed. Is your flat nice and warm? People say that Melbourne is very cold in winter but I suppose you have to put up with it as it is what you chose." The ordinariness of these communications and the narrator's ordinary struggle to differentiate herself from her mother is contrasted with her lofty mission to remake her understanding of Woolf ("the Woolfmother"), a feminist and literary icon she both looks up to as a kind of intellectual parent and feels should be put in her place.

De Kretser's writing is elusive and playful, jumping from one thread to the next and imposing layer over narrative layer. Deceptively simple language evinces weighty ideas, such as in a delightful passage that describes the narrator's first meeting with Olivia and her cousin Amabel:

"They were big, fair, marble-fleshed women who brought confidence to the way they occupied space. Amabel had the centre-parted hair and discontented mouth of a Botticelli Madonna. She was even taller than tall Olivia, and her round white face was a clock. The clock took its time inspecting my dress, my Docs and my offering of mangoes. It smiled as if alarmed."

Rife with signifiers of class, race, and ethnicity, de Kretser's narration portrays a world shaped by oppression and subjugation that refuses to admit to it — both in the university and outside of it. As in her analysis of Woolf's texts, the narrator's attempts to gain some advantage over Kit and Olivia, who are both presumably white and from well-off families, is in line with her general desire to exercise illicit control over something she knows is not supposed to belong to her, to "win" against the dull inequality that permeates Western society in the 1980s — and the 1880s, which is when The Years begins. Unsurprisingly, she grapples with the complications of Theory/theory and its relationship with practice, people, and real life. Even as, in her work, she successfully integrates observations about how British empire and colonization contributed to the progressive values that allowed for new freedoms enjoyed by The Years' female characters, she runs up against the limitations of feminism in her own day. Her supervisor Paula, whom she thinks of as Melbourne's Designated Feminist, is outwardly supportive but dismissive of the scope of her work.

The main timeline of the novel is related through the narrator looking back on her life, and we know from the beginning that she has become a novelist, perhaps inspired by an artist friend's advice for addressing her feelings about Woolf, based on Aristotle's "categorisation of human activities":

"'He distinguishes theoria, which increases knowledge, from praxis, which is action-for-itself. In between those two comes poiesis, which is action-for-making. Poiesis is creative. Make a film, paint, write a poem. Write back to Woolf.'"

Of all the examples of Theory/theory and practice/action given, one of the most striking and chilling is seemingly disconnected from the main narrative. Toward the beginning of the book, the narrator references a real-life essay, "Tunnel Vision" by Eyal Weizman, published by the London Review of Books. She explains Weizman's account of how Israeli military commander Aviv Kochavi credited poststructuralist and urban theory texts as inspiration for a raid on the West Bank, in which rather than moving as expected through streets and alleys, the Israelis smashed their way through buildings, terrorizing Palestinian families and driving resistance fighters out into the streets, where they were vulnerable and could easily be killed. In the larger context of de Kretser's novel, this stands as the logical extreme of a blandly strategic mindset let loose in a world where all possibilities are considered equally valid, where space is a commodity to be manipulated, exploited, and reinterpreted according to those in power and not a real place where real people live.

Theory & Practice is similar in substance to the recent novel But the Girl by Jessica Zhan Mei Yu. In both books, young Asian Australian women attempt to analyze racism in the work of famous white women writers — in Yu's case, Sylvia Plath — but also turn to creative work. This similarity would be more uncanny if not for the fact that both confront a basic inevitable reality in Western society: the moment when the gaze of intellectual authority, however temporarily and precariously, switches from one party to another. Theory & Practice and But the Girl legitimize their narrators' perspectives while also suggesting that this simple turning of the lens, their work of critically confronting historical and personal racism, is alone an insufficient response to the contradictions and frustrations that flood their current lives. These novels also bring to mind how Woolf and Plath, who both died by suicide, couldn't have anticipated the meticulous preservation, nor the widespread symbolic impact of their lives and work. At one point, de Kretser's narrator wonders of herself and other Woolf scholars, "Why were we reading her private diary?"

De Kretser's novel itself becomes an imaginative response not only to Woolf's novel, but to the greater question of how a person might choose to employ the knowledge they have and to live in the world with others. While the narrator's work on Woolf seems worthwhile, when placed beside what we come to know of her life as a whole, the Before and After of her grad school days, it shrinks when compared to the contours of her existence, of how she processes experience, of how we later understand that she was right about some things and wrong about others. Theory & Practice is relentlessly daring in its form, surprisingly generous in its exploration of events and ideas, and quietly provocative in the connections it makes.

![]() This review

first ran in the March 12, 2025

issue of BookBrowse Recommends.

This review

first ran in the March 12, 2025

issue of BookBrowse Recommends.

If you liked Theory & Practice, try these:

by Saou Ichikawa

Published 2025

A bombshell bestseller in Japan, a provocative, defiant debut novel about a young woman in a care home seeking autonomy and the full possibilities of her life—"a darkly funny portrait of disability" (Japan Times)

by Jessica Zhan Mei Yu

Published 2024

"Having been Jane Eyre, Anna Karenina and Esther Greenwood all my life, my writing was an opportunity for the reader to have to be me…"

The third-rate mind is only happy when it is thinking with the majority. The second-rate mind is only happy when it...

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.