Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

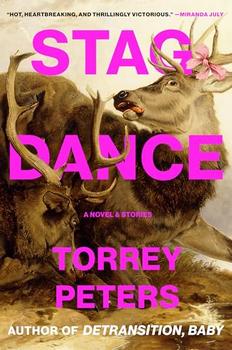

A Novel & Stories

by Torrey PetersSix chapters into the titular "novel" of Torrey Peters' collection Stag Dance, a big, burly lumberjack named Babe working in an illegal logging camp in early 20th-century Montana becomes annoyed when called upon to fix a jammed cable. "So before I had even appreciated my second cup of coffee," Babe gripes, "I found myself conscripted into unjamming someone else's blunder." This relatable and deftly delivered line is characteristic of the charming historical vernacular in which the story is written. I'm not sure how accurate to the time it is, but it's almost certainly a combination of period correct and pure invention. Glorious, it sparkles with wit, invective, and words that aren't in the average contemporary reader's (or perhaps anyone's) vocabulary, but are somehow easily comprehensible from context. A joyful oddity, it's utterly committed to its language and world.

This style is a delightful vehicle for Babe's exploration of gender and sexuality, a journey that begins when Karl Daglish, the camp boss, announces an upcoming dance for which lumberjacks can choose to wear a triangle of fabric between their legs, signaling they wish to be courted as women — or in the vocabulary of the story, "skooches." Babe finds himself unexpectedly aroused by the sight of the triangle over Daglish's crotch as he demonstrates its use, and in the ensuing days decides to wear a triangle himself, an act that leads to unforeseen drama.

Wearing the triangle gives Babe a chance to reflect on the role he has always played as a man, and to consider how women must feel in theirs: "The only medicine menfolk respect is a good clopping, yet the same menfolk insist that it is a certain reticence to hand out cloppings that makes the fairer sex fairer." Now trying out (internally and externally) identity as a woman, and hoping to attract the attention of men, Babe finds herself in this feminine dilemma. If she can no longer rely on brute strength to settle disputes, she decides, the secret is "to overexploit what hurt you do have." So she cries out her displeasure to her fellow workers for dropping her the night before during a rowdy blanket toss, telling one Johnny Jobs, "I hobbled to breakfast codgered like a geezer thanks to your carelessness … You gotta know that you can damage a person!"

The book as a whole consists of this central story, referred to as a novel, and three shorter stories. All introduce aspects of fluidity to gender, exposing the constructions beneath it. The strange, antiquated vocabulary of the novel and the use of first-person voices (and resultant lack of gendered pronouns) throughout the book merge to create a landscape in which gender is doubted more than established.

"Infect Your Friends and Loved Ones" puts a twist on the bigoted myth of a "trans contagion," showing a near-future world in which a group of trans women juggling resentments have let loose a virus that causes all humans to stop producing sex hormones, making the hormones — and, therefore, binary gender as we know it — a pricey commodity. "The Chaser" takes place in a Quaker boarding school and charts a romance between two roommates, one of whom may be a trans girl and the other, the narrator, stubbornly unwilling to admit to his feelings and what they might say about his sexuality. "The Masker" follows a character vacationing in Vegas who we are led to believe is plausibly a woman but hasn't decided how she wants to identify, hovering on what she sees as the periphery between cross-dressers and trans women. Summing up some of the stories in simple terms like this feels imperfect and impossible — Who are these people? What are their pronouns? How would they want to be spoken about, or would they (as seems more likely) rather not be spoken of at all? — because Peters' characters are drawn in a way that calls attention to the limitations of language, the elusive nature of identity, and the constructs that demand we choose one.

The characters' failures to either keep up with this demand or escape it form a pervasive pathos that gives gravity to the funny and absurd premises of the stories; how these qualities are balanced against each other varies. "The Masker," maybe intentionally, is the piece that most allows the reader to sit in a satisfying way with its sadness. Its ending, which is also the ending of the book, opens an unresolved space — both melancholy and intriguing — reminiscent of the conclusion of Peters' debut novel Detransition, Baby, in which the main character finds herself still painfully torn between two worlds. By contrast, "Infect Your Friends and Loved Ones" and "Stag Dance" feel a bit short and shut in on themselves. This correlates with the stubborn, closed-off attitudes of their characters, who, crushed beneath the boot heel of cisheteronormativity, try to free themselves in haphazard, surprising, and sometimes violent ways. That is likewise true of the narrator in "The Masker," but this story gives its character more breathing room and has more of a heart. "The Chaser" also leaves space for reflection above and beyond its ultimately quite disturbing picture of adolescent toxic masculinity, and readers who can stomach its depiction of (albeit somewhat unintentional) animal abuse are likely to find it memorable in more ways than one.

Detransition, Baby was a novel that felt significant for its nontraditional and quintessentially queer consideration of family and relationships. Brilliantly structured and resonant, its biggest flaw was arguably how it used the racialized presence of Katrina, a cis Asian woman, as a somewhat simplistic and reductive foil for its white trans characters, giving the story a strained and artificial feeling at times. Stag Dance, in contrast, is refreshingly free-flowing and singular, yet lacks the rich emotional core of Peters' previous book. But it also very much feels like more of an intentional mishmash than something that was ever meant to be a polished product. Peters notes that these stories were gathered from over a period of ten years, saying, "They were the stories I wrote to puzzle out, through genre, the inconvenient aspects of my never-ending transition—otherwise known as ongoing trans life—aspects that didn't seem to accord with slogans, 'good' politics, or the currently available language."

In keeping with this, Stag Dance reads like a batch of precious, wildly conceived writing that has thankfully been rescued from oblivion. It's the kind of writing that results from unprecedented, unpredictable bouts of creativity, the kind that, for reader or author, may never come again.

![]() This review

will run in the April 23, 2025

issue of BookBrowse Recommends.

This review

will run in the April 23, 2025

issue of BookBrowse Recommends.

If you liked Stag Dance, try these:

by Chuck Tingle

Published 2024

Bury Your Gays is a heart-pounding new novel from USA Today bestselling author Chuck Tingle about what it takes to succeed in a world that wants you dead.

Misha knows that chasing success in Hollywood can be hell.

by Anna North

Published 2022

The Crucible meets True Grit in this riveting adventure story of a fugitive girl, a mysterious gang of robbers, and their dangerous mission to transform the Wild West.

The only real blind person at Christmas-time is he who has not Christmas in his heart.

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.