Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

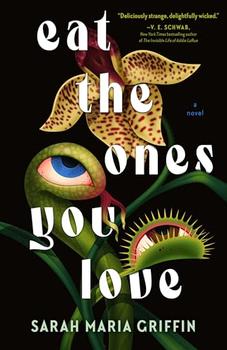

The beginning of Sarah Maria Griffin's Eat the Ones You Love is suffused with a draining pessimism: Shell, the main character, has lost her dream job in graphic design, broken up with her longtime fiancé, and moved back into her childhood home to live with her parents and two sisters. Shell's internal sense of immobility and inertia—being stuck in an inescapable, shoddy past—is paralleled by her trips to the nearby "rotting" Woodbine Crown Mall, an indoor shopping center long past its architectural and commercial heyday, which is slated for closure within the next year. Shell's backstory of personal and professional setbacks against the setting of dilapidated Woodbine sets up a timely critique of contemporary work culture, the present job market, and the supposed stability of domesticity—promises that prove to be false, fleeting, and broken.

At Woodbine, after responding to a "Help Needed" sign, Shell lands a job as an assistant to a beautiful florist, Neve, on whom she almost immediately develops a crush, and who introduces her to a tight friend group of Woodbine's longtime retail workers: Daniel, a hair stylist; Kiero, the owner of a print shop; and Bec, who works at a travel company. Thus Shell, whose life now revolves around Neve, her new friendships, and floristry, attains a renewed sense of belonging and direction that seems to overcome Woodbine's dreariness.

But the mall's failure, it becomes clear, can't be blamed entirely on the usual economic shifts and shopping trends; nor will Shell's story simply be about finding stability and purpose in late capitalism. Because at the center of Woodbine, hidden in plain sight in an emerald-green terrarium, thrives Baby, a carnivorous, man-eating orchid, who is lovingly tended by Neve. Shell may be the protagonist of Eat the Ones You Love, but its narrator—as Griffin reveals a few pages in—is Baby himself, who has an almost omniscient ability to access people's memories and thoughts. Obsessively in love with Neve, Baby wants to devour her heart, and is ruthlessly willing to use Shell and her new circle of Woodbine friends to do so.

Baby is a compelling addition to the haunted house and organic body horror subgenres. He kills people by devouring them, and is the reason shoppers keep going missing from Woodbine. His presence is menacing, far-reaching, and inescapable—his vines wrap and pulse at his will through the back rooms, walls, and foundations of the mall; and he can extend his spying consciousness beyond Woodbine by depositing his pollen into the air and onto Neve's flowers, which gives him surveillance over people who buy flowers from Neve's shop. "I had witnessed every single fantasy; no dream was private from me," he crows after invading Shell's psyche and seeing her imagine a date with Neve. His prey remain largely unaware of what Baby is doing, but they feel paranoid and psychologically tormented.

And yet because the book's main perspective is Baby's, the reader feels a twisted and disturbing sympathy for and intimacy with his feelings for Neve. As a character and narrator, he is darkly charismatic, hypnotic, and seductive, if evil and selfish. His hunger for Neve's heart is both terrifying and deliciously macabre:

"I would find a way to crawl through the o in her no. But that night … I merely held her. I exerted what little energy I had in the clipping she took from my centre that sat in the vase beside her. I unfolded my green shoots and vines onto the tabletop like compassionate little garden snakes, and I wrapped them up her arms and shoulders and throat like the lover I am, like the lover she needs. She never resists this. I softly wormed a single vine up to the corner of her mouth, like a kiss, and she opened up, smoke on her breath, in a kind of surrender."

For Neve to accept and, to a degree, reciprocate Baby's love—despite her many graphic encounters with the mangled corpses resulting from his gluttony—raises questions for the reader about her own complicity in Baby's murderousness. Yes, Baby is like something of an abusive lover, gaslighting her and instrumentalizing Neve's closest friends to bring her under his absolute control. And yet Neve does truly accept Baby, for all of his carnivorous appetites—she hides his secret; she cleans up his messes; she tells him that she understands why he does what he does. (If "man-eating" is simply his nature, the way a wolf or shark is carnivorous, can we really condemn Baby as evil? Neve stubbornly insists we can't.) Neve is essentially an unconditionally loving parental figure to Baby, someone who has carefully raised and cultivated him from his first days of consciousness; that makes their relationship more complicated, more interesting, and more incestuous than a straightforwardly "toxic" relationship.

Less dramatic interrogations of what makes a "healthy" or "unhealthy" interpersonal relationship arise through the characters' fixations on technology and social media. Shell's WhatsApp communications with her college friends are superficial and unemotional. On Instagram, Shell is compelled to keep up rose-colored appearances; after receiving Neve's job offer, she posts a coy picture of a bouquet with the caption "New Beginnings!" to try to provoke anxiety in her former fiancé, "if he bothered to look." Shell's social media following later explodes when she documents her floristry work, but the likes and comments remain shallow and impersonal, interactions that "pinged and pinged through the phone, the pleasure of it dispensed then dispersed."

One of the few relationships that overcomes this suspicion towards virtual, digital connection is the friendship that develops between Bec and Jenn, Neve's ex-girlfriend. Griffin periodically interrupts Baby's narration—and undercuts his control of the story—with intimate, worried emails between Jenn and Bec. The confidential alliance between the two women touchingly develops into loyalty and mutual care that becomes increasingly central in the final third of the novel—they work tirelessly together to unravel the ecological mystery and threat presented by Baby as he manipulates the chemistry between Shell and Neve.

Propelled by a horrifying and hypnotic villain, Eat the Ones You Love is creeping and abject in its organic horror and smart about the present day's crumbling institutions. As Griffin repeatedly emphasizes, using the central motif of flowers clipped in their prime to make enchanting bouquets, "all floristry was a dance around decay."

![]() This review

first ran in the April 23, 2025

issue of BookBrowse Recommends.

This review

first ran in the April 23, 2025

issue of BookBrowse Recommends.

If you liked Eat the Ones You Love, try these:

by Rivers Solomon

Published 2024

Welcome to Rivers Solomon's dark and wondrous Model Home, a new kind of haunted-house novel.

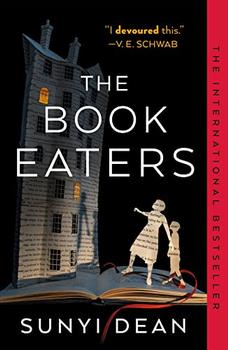

by Sunyi Dean

Published 2023

Sunyi Dean's The Book Eaters is "a darkly sweet pastry of a book about family, betrayal, and the lengths we go to for the ones we love. A delicious modern fairy tale." - Christopher Buehlman, Shirley Jackson Award-winning author.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.