Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

Esme Nicoll grows up surrounded by words. Starting in 1886, her father works for Dr. James Murray, editor of the Oxford English Dictionary. Since Esme's mother is dead, Dr. Murray and the rest of the staff look the other way whenever the girl accompanies her father to the Scriptorium — a grand word for what is actually a shed behind the Murrays' home in Oxford, England and not a place where inquisitive children would normally be welcome. Volunteers send in words to be defined and illustrative quotations to be compiled by the lexicographers. Esme sits on her father's lap and helps him open these letters. With one word per slip of paper, the Scriptorium is soon packed with evidence of hundreds of thousands of words.

Some get lost along the way, and others are purposely discarded. Five-year-old Esme rescues one from the floor. Sounding out the letters she recognizes, she deciphers the word "bondmaid." The second half of the word is familiar to her, reminding her of the family maid, Lizzie Lester, who effectively raises Esme. When Esme asks her father if she'll go into service like Lizzie, he tells her Lizzie is lucky to have work as a maid, but for Esme it would be a disgrace. This is the little girl's introduction to class differences. When, the next day, her father lets her search in the S pigeon-hole for "service," she finds a whole bundle of paper with a top-slip advising that there are "multiple senses." This is her first lesson in the multiple and conditional meanings of words.

As Esme comes of age, she continues gathering scraps of paper from the Scriptorium floor, but also picks up words and connotations from other women she meets. For instance, she becomes friends with the early suffragette Tilda Taylor, who redefines "sisters" for her as "women bonded by a shared political goal." At the covered market Esme meets Mabel O'Shaughnessy, a foul-mouthed peddler who teaches her vulgarities as well as "morbs," which she explains as a temporary depression to which women seem to be prone. Esme amasses new and forgotten words in a trunk labeled "The Dictionary of Lost Words." The suffrage movement and World War I loom large as the storyline enters the 1910s, with Williams taking readers behind the scenes in settings ranging from a hospital to the Bodleian Library at the University of Oxford. In the meantime, Esme finds ways to bring her rescued words to the attention of others.

The main action spans the 40 years of the original composition of the OED. That scope means that there is a lot of skipping forward in time, with subsequent chapters often set a year or a few years into the future. Especially in the first half, I longed for the narrative to slow down and linger with the characters in one time and place. While Williams effectively presents the sweep of Esme's life, I wished I could spend more time with this character on ordinary days. Despite the first-person narration, I never felt I knew her very well. In addition to this issue, there is a fairly melodramatic incident midway through the book.

Along with the history of the dictionary (the Author's Note and timeline at the end explain what is historical and what is fictional; while Esme is fictional, she interacts with some real people who lived at the time), I most appreciated the relationships Esme has with the various women in her life. Lizzie is a constant support, as is "Ditte" (who is based on Edith Thompson, a real-life figure), a spinster who contributes words to the dictionary. She is a close family friend whom Esme calls "aunty" and who encourages Esme in her ambitions.

Women's bonds and women's words are strong themes in this forthrightly feminist novel that, despite its flaws, would make a great book club selection. The omission of "bondmaid" is a real-life episode that inspired Williams, and Esme returns to that word several times, citing it as an example of how language can be used to put people in their place: "I realized that the words most often used to define us were words that described our function in relation to others. Even the most benign words – maiden, wife, mother – told the world whether we were virgins or not. … Which words would define me?" she asks. "Which would be used to judge or contain?" Williams uses her words to restore women to the male-dominated history of the OED.

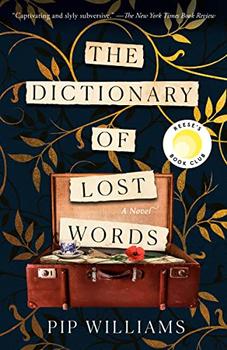

![]() This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in May 2021, and has been updated for the

June 2022 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in May 2021, and has been updated for the

June 2022 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

If you liked The Dictionary of Lost Words, try these:

by Nell Stevens

Published 2025

In a grand English country house in 1899, an aspiring art forger must unravel whether the man claiming to be her long-lost cousin is an impostor.

by Anne Curzan

Published 2025

A kinder, funner usage guide to the ever-changing English language and a useful tool for both the grammar stickler and the more colloquial user of English, from linguist and veteran professor Anne Curzan

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.