Page 1 of 1

There is 1 reader review for The Deepest South of All

Write your own review!

Cathryn Conroy

A Southern "Twin Peaks": An Eye-Popping, Almost Unbelievable, and Absolutely Fascinating Book

Cathryn Conroy

A Southern "Twin Peaks": An Eye-Popping, Almost Unbelievable, and Absolutely Fascinating Book

As I was mentally struggling with the best way to describe this book, the perfect line was uttered by one of the younger residents of Natchez, Mississippi: "This whole town is like a Southern Twin Peaks." Indeed.

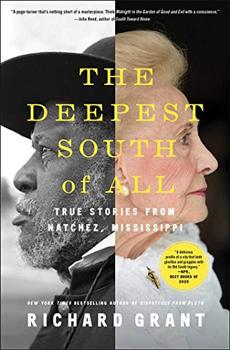

Englishman Richard Grant was promoting one of his books when he met Reginia Charboneau, a cookbook writer and chef from Natchez. She invited him to visit her hometown. He did. And took notes. This is his ultimate outsider-looking-in story of a deeply Southern town that is unlike any other in Mississippi:

• Gays are not only welcome here, but also they are beloved citizens.

• From 2016 to 2020, the mayor of Natchez was Darryl Grennell, a gay Black man who was elected with 91 percent of the vote.

• From 1930 to 1990, a Black woman openly ran a highly successful brothel right in the middle of town until her death at age 87. (An aggrieved customer set her on fire, but that's another story.)

• Oh, the gossip! Devout Christians attend prayer meetings where they actively engage in prayer gossip. As in, "Jesus, I'd like to pray for a dear, dear friend of mine, because I'm just worried sick about her. She's been seeing a married man, and I mean every day. What if her husband finds out?" Of course, everyone knows who the "dear, dear friend" is without her ever being named.

The only way to understand White Natchez society is to first understand there are two garden clubs. The elite White women who join these clubs don't actually garden. (Dirt? Worms? Ew!) Oh, and the two clubs have been in an intense, ugly feud for several generations. These clubs are a big deal. For example, the Pilgrimage Garden Club has 650 members and an annual operating budget of $1.2 million. The competing clubs host the annual event called Pilgrimage in which the grand antebellum mansions open their doors to paying visitors for tours led by Confederate-era costumed guides. To give the out-of-town visitors something else to do, the garden clubs put on a theatrical production about the history of Natchez, a production that is fraught with in-fighting and bad acting and resembles something more appropriate for a middle school play. Oh, and there are lots (and lots!) of libations all the time.

And then there is the other side of this Mississippi town. The Blacks, rightly so, view the segregated garden clubs as bastions of White supremacy. Grant says racial divisiveness is the "ongoing curse of Natchez." Racism means a far lower quality of life and economic prosperity for the town's Black population—from education to jobs. Grant offers an in-depth and very personal discourse on both the history and current situation of what it's like to be Black in Natchez, Mississippi—from slavery to the Civil War and Jim Crow to the civil rights movement.

In addition, Grant intersperses the chapters about modern-day Natchez with some of its colorful history, including the story of a Natchez slave that was an African prince. It's a riveting tale that reads like fiction, but it's true.

Throughout the book, the author discusses the legacy of slavery that built the town and the antebellum homes, as well as provided the economy that allowed Natchez to thrive. He spots overt and covert racism and calls it out. He isn't afraid to ask the White residents the hard questions, including their almost universal denial of slavery and racism, although the answers are often just steely looks.

This is an eye-popping, almost unbelievable, and fascinating narrative about an eccentric small town in Mississippi populated with outlandish characters that has somehow managed to hang on to its Southern charm, history, and tall tales. Grant's observations are pithy, hilarious, and perceptive.