Book Club Discussion Questions

In a book club? Subscribe to our Book Club Newsletter and get our best book club books of 2025!

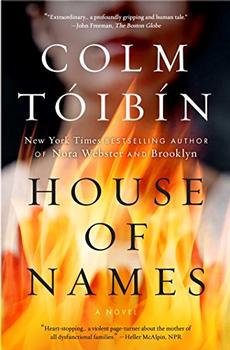

For supplemental discussion material see our Beyond the Book article, Women who Scheme: The Female as Villain in Greek Tragedies and Beyond and our BookBrowse Review of House of Names.

Please be aware that this discussion guide will contain spoilers!

A Note From The AuthorWhen I had finished my novel

Nora Webster, which followed

Brooklyn, I knew that I would not write about Enniscorthy again for a while. I felt as though I had dreamed the town where I grew up out of my system.

One day, a friend suggested I should look at the story of Clytemnestra, the figure in Greek theatre, who murdered her husband, Agamemnon, and was in turn murdered by her son, Orestes, egged on by his sister Electra.

At first I was not sure. But I became interested in re-seeing this fierce and ferociously dramatic family. I saw motive. I saw love and hatred and jealousy. I saw most of the book happening in a single space, almost like a town, a place full of secrets and whispers and rumors.

Even though

House of Names is animated by murder and mayhem and the struggle for power, it is still a story about a single family as it tears itself asunder. No matter what happens, I was dealing with family dynamics, something I have been dramatizing in all my books: the same emotions, the same regrets, the same elemental feelings.

Only this time it was happening in ancient Greece rather than in the streets of Enniscorthy.

—Colm Tóibín

Questions- Clytemnestra speaks of "a hunger I had come to know too and had come to appreciate" (page 3) in the opening pages. What does this hunger signify? Why do death and appetite come together in these early scenes, particularly for Clytemnestra?

- Agamemnon and his men seem to believe in the gods so much that they will sacrifice Iphigenia unquestioningly, while this act cements for Clytemnestra "that I did not believe at all in the power of the gods" (page 32). Do you think she is the only one with doubts?

- Why does Clytemnestra brush Electra aside after Iphigenia's death? Could the consequences of Clytemnestra's "first mistake" (page 40) with Electra have been avoided?

- Was Clytemnestra wise to trust in Aegisthus? What are his true motives? Would you have relied on him in Clytemnestra's place?

- As Clytemnestra leads Agamemnon to the bath where she will murder him she feels a "small pang of desire," "the old ache of tenderness" for him (page 62). Why do these feelings spring up? Why do they not give her second thoughts, instead of strengthening her resolve?

- After Orestes is taken, Clytemnestra still imagines "exerting sweet control" over Aegisthus and Electra and "the possibility of a bloodless future for us" (page 69). How is she able to be so optimistic at this point?

- With Leander and the guards, Orestes feels that "if only he could think of one single right question to ask, then he would find out what he needed to know" (page 101). Why is this? How does this feeling characterize Orestes throughout the novel?

- When Orestes needs to attack one of the men pursuing him, he thinks he "could do anything if he did not worry for a second or even calculate" (pages 124–25). How does this kind of thinking play out in his future actions?

- Why does Mitros refuse to share with Orestes and Leander what the old woman told him would happen to them in the future (page 138)? How does their time with the old woman, Mitros and the dog shape both Orestes and Leander?

- Does Electra mourn Iphigenia? Why does Electra so completely spurn Clytemnestra, envisioning her death in the sunken garden with a smile (page 147)?

- How is the dinner where Electra wears a dress of Iphigenia's and attempts to catch the eye of Dinos a turning point for her?

- Why does Electra tell Orestes they live in a "strange time . . . when the gods are fading" (page 206)?

- When Mitros' father talks with Orestes about Clytemnestra and Aegisthus, Orestes says Clytemnestra "did not kill Iphigenia," and Mitros says the gods demanded that and continues to lay all blame at Clytemnestra's feet (page 217–19). Eventually, Orestes is swayed by Mitros' insistence that Clytemnestra is in control of all and must be punished. How are they able to brush aside Aegisthus' and even Agamemnon's actions?

- As Orestes prepares to kill his mother he envisions "what was coming as something that the gods had ordained and that was fully under their control" (page 234). But who else might be controlling Orestes in this moment?

- After Clytemnestra's death, how do Electra and Orestes continue to reflect and be affected by their mother?

- Names—calling them, invoking them, remembering them—are significant throughout the novel. What power do they hold? Discuss what names mean to the old woman, the elders who lost their sons, Orestes and Leander and Clytemnestra.

- House of Names is told from Clytemenestra's, Orestes' and Electra's points of view. How do their different perspectives shape the narrative? What might Agamemnon's account be like?

- In his note about how he came to write House of Names, Tóibín says that "even though House of Names is animated by murder and mayhem and the struggle for power, it is still a story about a single family . . . something I have been dramatizing in all my books: the same emotions, the same regrets, the same elemental feelings." Are there insights you draw from this novel akin to those you might draw from a more conventional family story?

Enhance Your Book Club

- The Travelling Players is a 1975 Greek film directed by Theodoros Angelopoulos that reinvents Aeschylus' The Oresteia and traces the history of mid-twentieth century Greece from 1939 to 1952. Watch the film and discuss its parallels with House of Names.

- Read Eugene O'Neill's play cycle Mourning Becomes Electra, a retelling of The Oresteia. Contrast Tóibín's version of the story with Eugene O'Neill's.

- Read Colm Tóibín's The Testament of Mary. How is Mary like Clytemnestra? How are they different? What might have drawn Tóibín to reinterpret these iconic women?

Unless otherwise stated, this discussion guide is reprinted with the permission of Scribner.

Any page references refer to a USA edition of the book, usually the trade paperback version, and may vary in other editions.