Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

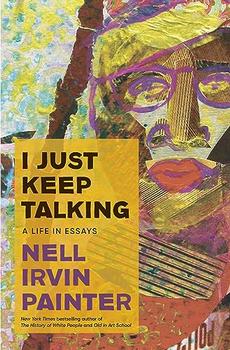

A Life in Essays

by Nell Irvin PainterIntroduction

EGO HISTOIRE

It's a good thing I didn't die young. Meaning it's a good thing for my reputation that I didn't die during the full-blown era of White-male default segregation, discrimination, and disappearance that wound down only yesterday. I would have disappeared from memory, just another forgotten Black woman scholar, invisible to history and to histography. So much in me-a dark-skinned Black woman, always very smart, born in Houston in the Houston Hospital for Negroes in 1942-was suited for disregard. No family drama. My parents were married; they stayed married in as good a heterosexual marriage as Americans born in 1917 and 1919 could have and that lasted seventy two years-until my mother's death. We were never poor, though never rich, and physical violence and addiction played no part in my family. My parents supported me emotionally and materially for more than forty years. There's not much there in my life to match what my country likes to recognize as a Black narrative of hurt. I remember speaking about Old in Art School in Seattle to a wonderful, warm audience largely of women. A questioner asked me what I do for healing. "Nothing," I said. "I'm not broken." Not broken, but on occasion frustrated, indignant-self-righteously pissed off with cause, often exhausted, but mostly and permanently grateful for the people who have protected me, mentored me, supported me over so many decades. Without you, there would be no me.

My Blackness isn't broken. It faces a different way. Mine is a Blackness of solidarity, a community, a connectedness to other people who aren't known personally, of seeing myself as part of other people, other Black people. My Blackness also brings with it an understanding of how other people see oneself, a seeing that can be hurtful, but not one's own fault. What W. E. B. Du Bois called "twoness" is not merely an exhausting from-the-inside/from-the-outside identity, but also an ability to understand more than one way of seeing oneself in the world, an awareness that some non-Black Americans lack. The history of that seeingness brings with it strategies, its armor-usually communal-for fending off hurt. Those strategies of protection aren't always as robust as society's strategies of meanness, which are legal, financial, and personal. But ours are better than nothing, better than going into a cruel world naked and unarmored. I wish other Americans weren't so wedded to an individualist identity, that they could understand themselves more as connected to other people, locally and nationally, and less with having to do with guns and not caring how one's behavior endangers other people. I wish we had more solidarity, even if that makes me sound like a socialist.

My Blackness celebrates itself through art-music, dance, painting, talking, writing-what I term Black studies. Since the opening of the cultural realm in the twenty-first century, people of all sorts have been able to savor the art of Black artists, and I'm proud to say that early on in this century that is no longer new, I brought Black visual art to the fore in my narrative history Creating Black Americans: African-American History and Its Meanings, 1619 to the Present (2006). Black history is full of pain, but it's full of something more: creativity. Since my years in art school, I've been adding to that legacy through my own visual art, including what you see in this book.

At the same time, I think it's right to tally up the injuries of slavery, to the enslaved and to their descendants in psychic and material terms-to the nation in its politics and social norms. What lives in me, specializing in post-Civil War history as a historian, are the wrongs that came after slavery and that live with me as experiences in my historical research, the terrorism, the lasting imprint of the politics of White supremacy enforced through violence, experienced for me intellectually, but harrowing nonetheless.

Excerpted from I JUST KEEP TALKING by Nell Irvin Painter. Reprinted by Doubleday, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2024 by Nell Irvin Painter.

Polite conversation is rarely either.

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.