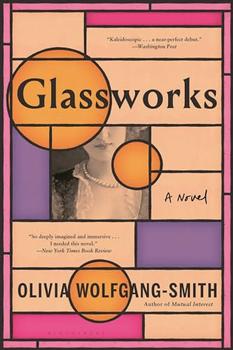

Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

This article relates to Glassworks

Olivia Wolfgang-Smith's novel Glassworks begins with the heroine employing a Czech glass artist to create a collection of realistic flora and fauna for her university in Boston. In interviews, the author has stated that she was inspired by Leopold and Rudolf Blaschka, a father-and-son team who created thousands of remarkably detailed biological models in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Olivia Wolfgang-Smith's novel Glassworks begins with the heroine employing a Czech glass artist to create a collection of realistic flora and fauna for her university in Boston. In interviews, the author has stated that she was inspired by Leopold and Rudolf Blaschka, a father-and-son team who created thousands of remarkably detailed biological models in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Leopold Blaschka (1822-1895) was born into a glassworking family that traced its roots in the craft back to 15th century Vienna. Although as a child he dreamed of being a painter, he was apprenticed to a jewelry maker and gem cutter, eventually joining his father in the family glass business. He cut his teeth in the trade creating costume jewelry and glass eyes for those needing a prosthetic as well as taxidermists. Over time, Leopold became incredibly skilled at lampwork, a technique whereby glass rods are heated (originally over an oil lamp, but by Leopold's day alcohol was used as fuel) and then, once the material is soft, pulled into the desired shape. He took over the enterprise on his father's death in 1851.

Leopold began making glass plants for his own amusement sometime around 1857. History doesn't record how, but these creations came to the notice of Prince Camille de Rohan, a horticultural enthusiast who'd created a world-famous garden at one of his estates. He befriended Leopold and often provided him with tropical plants from his greenhouses for study. More importantly, he introduced the glassmaker to Professor Ludwig Reichenbach, the director of the Natural History Museum in Dresden. Impressed with Leopold's work, Reichenbach commissioned him to make a collection of glass sea anemones in 1863 . Other museum directors took notice of the remarkably detailed creations, and additional contracts followed. Soon Leopold's works were being sold to museums worldwide and manufacturing glass sea invertebrates became his primary business. His son Rudolf began collaborating with him in 1870 and became a full partner in 1876.

Meanwhile, in the United States, Professor George Lincoln Goodale, the first director of Harvard's Botanical Museum, was searching for an aid to help him instruct his students about the anatomy of flowers. Models of the day were inadequate; pressed specimens were two-dimensional and crumbled over time, while the three-dimensional versions made from papier-mâché or wax lacked detail. Goodale saw a few of the Blaschkas' invertebrates at an exhibition hosted by Harvard's natural history department and decided to travel to Dresden in 1886 to see if the business could make flowers as well. He commissioned a few sample pieces, and although they were broken in transit, the items were nevertheless impressive.

Goodale enlisted a talented pupil named Mary Ware to convince her mother Elizabeth to fund a collection of the Blaschkas' flowers. Elizabeth agreed, dedicating the collection in memory of her late husband, Charles Eliot Ware.

The Blaschkas were at first reluctant to sign a contract with Harvard. Their business was thriving and the university project would mean cutting back on their work for other institutions. They were ultimately convinced, however, and from 1887-1890 they split their time between creating Harvard's flowers and sea creatures for other clients; in late 1890 they signed a 10-year contract, agreeing to work exclusively on Harvard's pieces. In 1895, Leopold died, and Rudolf continued the project alone. Over 50 years, the Blaschkas produced some 4,400 glass models representing more than 830 plant species for the university's collection. In addition to flowers, the duo produced glassworks representing diseased fruit, the insect pollination of plants, and the life cycles of ferns and fungi.

The flowers themselves remain marvels of creation, and when one looks at them it's nearly impossible to believe they're made of glass. And yet, Leopold claimed he used no special techniques in creating his works, crediting their beauty to his long family history in the trade as well as an attention to detail. Modern experts continue to admire their accuracy; no scientist has been able to find fault in any of the pieces.

Harvard's collection remains the largest and best-known compilation of the Blaschkas' work. Known officially as the Ware Collection of Blaschka Glass Models of Plants or, more commonly, The Glass Flowers, it's permanently housed in the Harvard Natural History Museum in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Photograph of a glass apple blossom in the Glass Flowers Gallery at the Harvard Museum of Natural History. This image belongs to the Digital Collection of the Harvard University Herbaria.

Filed under Music and the Arts

![]() This "beyond the book article" relates to Glassworks. It originally ran in June 2023 and has been updated for the

February 2025 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

This "beyond the book article" relates to Glassworks. It originally ran in June 2023 and has been updated for the

February 2025 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.