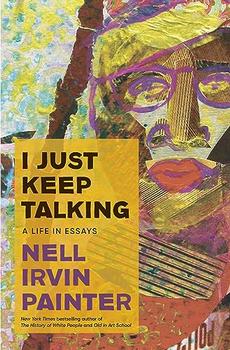

Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

A Life in Essays

by Nell Irvin PainterThis article relates to I Just Keep Talking

It was May of 1851 when 54-year-old Sojourner Truth took the stage. Truth, who would become one of the most famous women of any race of the nineteenth century, spoke her personal testimony to the mostly white audience at the Women's Rights Convention in Akron, Ohio. She was the only speaker who had been enslaved and the room was captivated by her height, forthrightness, and passion.

It was May of 1851 when 54-year-old Sojourner Truth took the stage. Truth, who would become one of the most famous women of any race of the nineteenth century, spoke her personal testimony to the mostly white audience at the Women's Rights Convention in Akron, Ohio. She was the only speaker who had been enslaved and the room was captivated by her height, forthrightness, and passion.

In the audience that day was Marius Robinson, a secretary for the convention who was speedily taking notes. His account of Truth's speech was published in the abolitionist newspaper The Anti-Slavery Bugle three weeks later. One of the more powerful moments of the speech as recorded by Robinson was when she said, "I can't read, but I can hear. I have heard the Bible and have learned that Eve caused man to sin. Well if woman upset the world, do give her a chance to set it right side up again." Robinson wrote that Truth concluded her speech with, "But man is in a tight place, the poor slave is on him, woman is coming on him, and he is surely between a hawk and a buzzard."

Twelve years later in 1863, abolitionist and women's rights activist Frances Dana Gage, who had been

the conference chair at the convention, published her own account of what had happened. She described Truth as "tall" and "gaunt" in a gray dress and a white turban. Gage noted that Truth marched to the front row like a queen. She had been quiet the first day of the convention. The second day, when white women wouldn't defend women's equality, Truth stood up.

Gage, in rewriting the testimony by Truth, gave her a slave dialect she didn't possess, a plantation Gullah-like language. Truth was born in New York, had a Dutch accent and had never been a southern slave, didn't speak a tongue similar to that of southern slaves. But Gage wrote her words as if she was from South Carolina or Georgia to make her fit the stereotype of an ex-slave: "Nobody eber helps me into carriages, or ober mud-puddles, or gibs me any best place! And ar'n't I a woman? Look at me! Look at my arm! I have ploughed, and planted, and gathered into barns, and no man could head me! And ar'n't I a woman? I could work as much and eat as much as a man—when I could get it—and bear de lash as well! And ar'n't I woman? I have borne thirteen chillen, an seen 'em mos' all sold off to slavery, and when I cried out with my mother's grief, none but Jesus heard me! And ar'n't I a woman?"

According to historical records, Truth didn't have thirteen children. She had five. James, her

firstborn, died in childhood. Her son Peter was sold but she made history in 1828 when she was the first black woman to win a legal victory against a white man to secure a child's freedom.

Gage's version of Sojourner Truth, who repeated four times "Ar'n't I a woman," was new to Marius Robinson. It just so happened that Truth, a friend of his, had stayed with him and his wife during the year of the convention. It is documented that the version of her speech that he recorded for The Anti-Slavery Bugle is one that he shared with her, and it is generally believed that he received her approval before he published it.

"We cannot know exactly what Truth said at Akron in 1851," wrote historian Nell Irvin Painter in

her book Sojourner Truth: A Life, A Symbol. "She put her soul and genius into extemporaneous speech, not dictation, and lacking sound recordings or reliable transcripts, seekers after Truth are now at the mercy of what other people said that she said."

Painter revisits Truth in "Difference, Slavery, and Memory: Sojourner Truth In Feminist Abolitionism," appearing in her essay collection I Just Keep Talking. She disentangles Gage's account, noting that "she [Gage] dramatized Sojourner Truth's presence. Gage supplies this almost Amazon form which stood nearly six feet high, head erect and eyes piercing the air like one in a dream." It makes sense, in a way, that Gage took such liberties without permission. Truth's prior enslavement gave her an authenticity white women abolitionists like Gage couldn't obtain and so her presence as an abolitionist was romanticized and at the same time necessary.

"Ar'n't I a woman?" flourished for the next century despite the wrongness of the question and its

fictional attribution. Gage had no idea, after the pen left her hand, that she had altered history. A black woman who should have been invisible became a celebrity because of four words she never said.

Sojourner Truth in the 1850s, from Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery via Look and Learn

Filed under People, Eras & Events

![]() This article relates to I Just Keep Talking.

It first ran in the May 15, 2024

issue of BookBrowse Recommends.

This article relates to I Just Keep Talking.

It first ran in the May 15, 2024

issue of BookBrowse Recommends.

He has only half learned the art of reading who has not added to it the more refined art of skipping and skimming

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.